–Republic of Palestine republishes this article, originally published on The New Arab website on April, 14, 2025, by Vijay Prashad.

Palestinians have a rich pedigree in anti-colonial struggles, just look at the Spanish Civil War and the life of Muhammad Najati Sidqi, says Vijay Prashad.

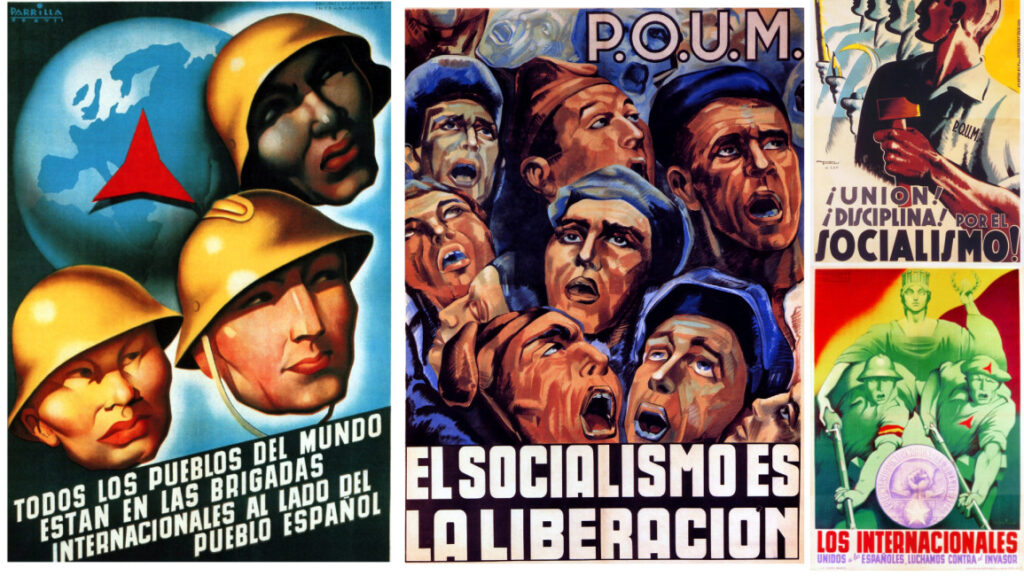

In 1936, tens of thousands of people from around the world came to Spain to defend the Republic against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. Called the International Brigades, the men and women who came to fight came from around the world: from Bulgaria to India, from China to Palestine.

Yes, Palestine. It is very hard to know who came from Palestine to Spain, because the records are not accurate.

For example, Mahmud al-Atrash al-Maghribi, a Palestinian Communist, left behind an autobiography — Path of Struggle in Palestine and the Arab Levant: The Memoirs of the Communist Leader Mahmud al-Atrash al-Maghribi; remarkably, it is often said that he was in Spain, even though there is no mention of a journey to Spain in his otherwise detailed and informative autobiography.

But we do know that at least three people from Palestine came to Spain: Ali Abd al-Khaliq, Fawzi Sabri Nabulsi, and Muhammad Najati Sidqi.

They were members of the Palestinian Communist Party and came to Spain via the Communist International. Sidiqi left behind an autobiography — Mudhakkarat Najati Sidqi – which was published posthumously in Beirut by the Institute for Palestine Studies in 2001.

In his autobiography, Sidqi recalls how the Spanish Republicans took him to the frontline so that he could, in Levantine Arabic, shout to the Moroccan soldiers who fought in Franco’s Ejército de África — Army of Africa.

They were transported by Nazi German Junkers from Morocco to Spain to form the main troops at the front against the Republican army. “Listen brothers,” Sidqi yelled across the front. “I am an Arab like you, coming from a distant Arab country. I beseech you brothers to abandon the ranks of your generals, who are oppressing you in your country. Come to our side where you will be well-treated and given a daily allowance. Those of you who do not want to fight will be returned to his land and family. Viva el Front Popular Viva la Republica. Viva Marruecos!”

As far as Sidqi recalls, no Moroccan soldier defected to the Republicans. Perhaps because they, speakers of Darija, or Moroccan Arabic, did not understand him at all.

In his book Diario De La Guerra De España (1938), the Soviet journalist for Pravda Mikhail Koltsov recounted an anecdote about Sidiqi. Because of the failure of defections, Sidiqi took a name more suitable to the Moroccan Arabs – Mustafa Ibn Jala; under this name, Sidiqi wrote for the Spanish Communist paper, Mundo Obrero.

The dead bodies of Moroccan soldiers had leaflets written by Ibn Jala in her pockets. These were written in Darija but did not generate desertion largely because of the high rate of illiteracy of rural Moroccans. Koltsov, by the way, was a close friend of Claud Cockburn, the father of Alex Cockburn of Counterpunch.

- To be Palestinian is to be anti-colonial

During his time at the front, Sidqi documented the war for the Arab press.

In the Syrian Communist Party journal Sot a-Sha’ab — Peoples’ Voice — of 15 May 1937, he wrote his first article from Spain. But of all the pieces that have been tracked down, the longest is an article, ‘Five Months in Republican Spain: The Memoirs of an Arab Fighter in the International Brigades’, in al-Tali’a — The Vanguard, Beirut — in June 1938.

In Barcelona, Sidiqi is greeted by a Catalan commander, who asks him why he is not in the militia. When Sidiqi says that he is an Arab, the commander is astounded. “But the Arabs,” he says, “are with Franco and his bloodthirsty aides.”

The commander tells Sidiqi about how the Moroccan army, the Army of Africa, had turned on the great leader of the Rif War, ‘Abd al-Karim, in 1925 and defeated him — ‘Abd al-Karim was Che Guevara’s role model for guerrilla warfare, and it is said that they met in the Moroccan embassy in Cairo when Che visited Egypt and Gaza in 1959.

Sidiqi responds to the commander: “I’m not the only Arab here! There are many now in the International Brigades, and others will come, too. Even those Arabs who are now among Franco’s ranks, their eyes will be opened, and they will desert and join your forces. I have learned of many whose eyes have been opened and are waiting for the opportunity to defect to the Republican camp. In our Arab countries, there are 70 million Arabs whose affinity lies with the Spanish Republic, who advocate for democracy, because their Arab civilization, their venerable historical traditions, are built upon a foundation of true democracy.” This is from Sidiqi’s memoir.

Sidiqi left Spain and returned to Lebanon. There, he threw himself into the task of anti-fascist work. Part of this work included the writing of a book, published in May 1940 called al-Taqalid al-Islamiyya wa-i-mabadi al-naziyya: Hal Tattafiqan? – The Islamic Traditions and Nazi Principles: Can they Harmonise?.

This was Sidiqi’s attempt to ensure that no aspect of fascism came into the Arab struggle against colonialism, despite the temptation to ally with the enemy of the Arab nation — the British Empire.

His experience in the Communist movement and in Spain had left a deep mark on him. After the war and after the Nakba that led to the expulsion of Palestinians from their homes, Sidiqi became a translator, bringing mainly Chinese and Russian novels into Arabic.

During this genocide in Gaza, I have often thought about people such as Sidiqi who broaden our understanding of solidarity. To be in solidarity, for them, was not to be with someone else or in someone else’s struggle. It was to be with themselves.

These were people who wanted to expand their own humanity, to fight to defend humanity on the doorstep of Madrid. If Madrid fell, they felt, their own humanity would be compromised. “Madrid is the heart,” wrote W. H. Auden in his superb poem, Spain, 1937.

Pablo Neruda went a step further, publishing a book of poems called Spain in the Heart in 1937. This was the power of internationalism offered to men such as Sidiqi by the Communist International.

They felt that it would be hard to be human in a world where such harm is done to others and to the planet, if they did not do something, anything to stop it. To become briefly a human is possible only by struggle, only by the act of undoing harm to oneself or to others.

The example of people such as Sidiqi helps us understand why it was the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic (DDR) that trained and armed the Palestinian fedayeen — as explained by Lutz Kreller in DDR und PLO, 2017, and why it was that the Japanese Red Army came to join the fight in the Levant against the Israeli occupation.

One of the Japanese anti-colonial fighters, Shigenobu Fusako worked in Beirut with Ghassan Kanafani at al-Hadaf and was then falsely arrested and held in prison for twenty-one and a half years.

Last year, Fusako published パレスチナ解放闘争史 1916-2024 — History of Palestinian Liberation Struggle 1916-2024, which she dedicated “with all my heart to all the Palestinians who are fighting for their freedom and liberation and are struggling in the face of the genocide being committed against them.”

There is no apathy here. It reminds me of the last part of Neruda’s Explico Algunas Cosas — I’m Explaining a Few Things, 1947:

Treacherous

generals:

see my dead house,

look at broken Spain:

from every house burning metal flows

instead of flowers,

from every socket of Spain

Spain emerges

and from every dead child a rifle with eyes,

and from every crime bullets are born

which will one day find

the bull’s eye of your hearts.

And you will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

Vijay Prashad is the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is the editor of Letters to Palestine (2014) and his most recent book is (with Noam Chomsky), On Cuba (2024).

Follow him on X: @vijayprashad