This article was published on the Lebanese website Al-akhbar on July 10, 2025.

By: Mousa Alsadah

Exactly ten years before he was martyred in a Zionist airstrike, along with his brother, sister, and their children, Alaa, Yahya, and Muhammad, the martyred Palestinian writer and academic Refaat Al-Areer wrote the following in the introduction to his book Gaza Writes Back: “The more brutal Israel becomes, the more reasons the Palestinians of Gaza find to cling to life and to remain on their land.” Dr. Refaat continues: “Many in Gaza have sworn to fight in its defense, many others have sworn to protect the fighters, and some Gazans have taken refuge in their pens or keyboards, vowing to expose Israel’s aggression through writing.”

No one could have imagined the extent to which the people of Gaza would remain loyal to this pledge, or how long this bond between escalating brutality and the will to survive and standing up to it would endure, using all means at their disposal, foremost among them the pen and the written word. In the enemy’s logic, “what cannot be achieved by force can be achieved by more force,” but what brutal force can be unleashed on a human society more than genocide?

Yes, we must be careful not to romanticize resilience, to obscure the magnitude of the tragedy, injustice, inaction, and complicity by exporting an image of the invincible Gazan superhero, as if they were not human. We merely work to satisfy our imagination of superhuman heroism, using it to cover up the shame of our failure to them. Before they are heroes, they are oppressed, and in a state of alienation and loneliness unlike any we have seen before. And before we forge our relationship with the hero, we must forge our relationship with this oppressed person. The former gives a false sense of comfort by glorifying him. The latter is a relationship that requires work and abandoning comfort for the sake of victory. The two definitions do not cancel each other out. What we must do is understand that these heroes are, above all, oppressed, or, in Fanon’s words, “the wretched of the earth.”

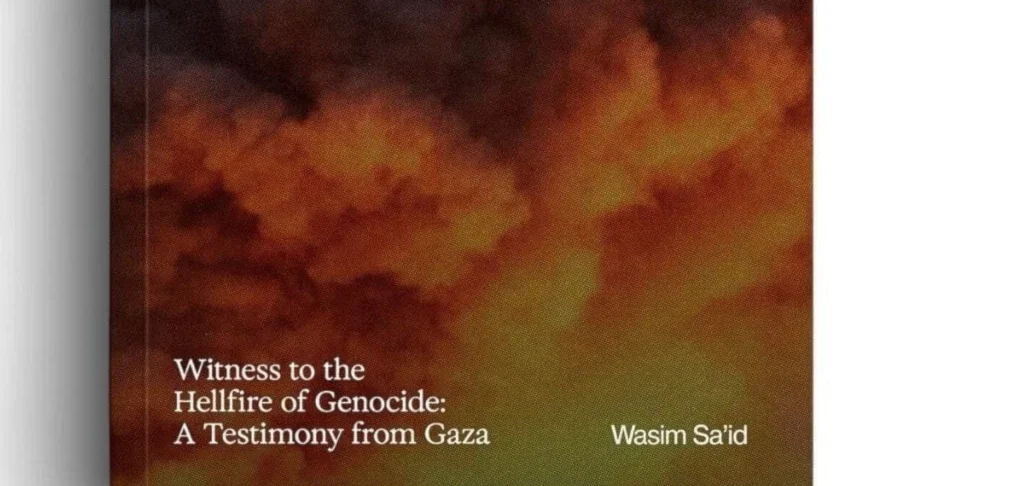

Wasim Said, the oppressed hero, a 24-year-old physics student at the Islamic University, provides an answer to the extent of the pledge that martyr Refaat Alareer told us about. Armed with a pen, paper, and a small mobile phone, he wrote his testimony during the genocide, which was compiled in a book: Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza (soon to be published by «Dar al-Thaqafa Academy» and «Dar al-Farabi», and in English by «1804 Books» and the «Popular Center for Palestine» in the United States, and «Liberated Texts» in the United Kingdom).

Exactly 100 years ago, Zionist theorist Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote his famous essay “The Iron Wall,” declaring that “the Arabs will not surrender until there is no hope left, when there is not a single visible breach in the iron wall.” Wasim’s act of writing this book from northern Gaza, however, is the hope itself, one of the breaches that even genocide could not break. Wasim’s writing, in these exceptional circumstances, proves that Jabotinsky—and every Zionist theorist who came after him—was wrong, reaffirming that Dr. Refaat alareer was right.

Genocide is an exceptional circumstance, the ultimate manifestation of the intensified death and killing against the human race. While literature on genocides usually documents them after they occur, through the testimonies of survivors, this book documents them as they happen. Zionist planes fly overhead, their buzzing and the sound of their drones hovering around him, while pen and paper are sheltered under the canvas of a displacement tent, he writes in the shadows of hunger and starvation.

The author did not recall these moments from distant memory, but lived them moment by moment as he wrote them down. This is not writing about death, but writing in the midst of it, surrounded by it. This is the first thing the reader must understand: every scene documented in this text, every scream and every explosion, was not merely a subject for writing, but a living reality that intruded upon the writing itself. The act of documentation itself needs to be documented. So, when you read, don’t ignore the sounds of planes, explosions, and ambulance sirens that still pierce every line and sneak between the words, because they are simply part of the text itself.

The act of documentation itself needs to be documented. So, when you read, don’t ignore the sounds of planes, explosions, and ambulance sirens that still pierce every line and sneak between the words, because they are simply part of the text itself.

In late April, my friend Louie Aldi sent me the first draft of the book, accompanied by his comment: “You must read this! It is our duty to publish it.” This marked the beginning of my communication with Wasim. In the first audio recording he sent me, Wasim explained his reasoning and motivation for writing this testimony. His motivation reflects what goes through a person’s mind when they are surrounded by death in all its forms and fragments. Wasim pointed to the need to resist this collective erasure of families, who are being killed and exterminated, refusing to let them disappear forever. Someone had to give them meaning and preserve their memory. This is what Wasim set out to do.

But Wasim didn’t write after survival. He wrote in the narrow space of life amidst the throng of massacres. That’s why he repeats in every recording and message between us: “My goal is to leave a mark” and “not to be forgotten. “The book was his personal answer to a question that kept echoing in the mind of every Gazan: Will I die and be forgotten? Will my death pass as if I never existed? Or as one of them bitterly put it: “If you’re lucky and are martyred, shrouded, and given a funeral, you’ll be remembered for two hours, and then it’s all over, as if you never existed.” Wasim wrote to break this oblivion, to give a trace to those who have passed away, and to give those who remain the comfort that there are those who bear witness and record, in the midst of death, that they were here.

This is precisely where Wasim’s bravery is revealed, and perhaps in this work, he embodied the bravery of Gaza. A young man in his early twenties, he rebelled against the imposed end and refused to be silently erased. In circumstances that were absolutely the most difficult in history for any human being: death on the largest scale, the most modern weapon, and the greatest collusion the age has witnessed, Wasim wrote, wrote with pen and paper.

He spoke to me at length about moments of doubt regarding the meaning of his work, about how giving up almost destroyed everything, about those moments when he came close to stopping, but continued nonetheless. For Wasim, writing was not merely an expression, but a physical act of answering the biggest philosophical question: What does it mean to live? For him, this meaning was not a contemplation, but an action: if I don’t write, it’s as if I never existed.

Because he is from Gaza, Wassim’s response was not a selfish individual salvation, but rather a collective one. In the text, you see how he is confused, how ashamed to talk about himself, and how he asks: “What about my community? What about those who were not given the opportunity to write?” The text quickly became written about them, on their behalf, in one of the noblest forms of self-sacrifice. Wasim did not carry a weapon; his only response was: with my pen on behalf of all of you.

This collective dimension is clearly present in the text, as it is in Gaza, in the solidarity of people in the midst of genocide. Genocide, as a concept, is not just mass murder, but a systematic colonial process aimed at dismantling the colonized society, demolishing its material structures, institutions, and self-organization. However, at its deepest core, it is an attempt to destroy its moral structure, transforming society into scattered masses, individuals preying on each other for survival.

This testimony stands out, not only in its daily documentation of acts of generosity, altruism, honesty, and cooperation, but also in the fact that, under conditions of genocide, it is itself evidence of the remarkable cohesion of this society’s moral structure. This, precisely, is what the field of anthropological studies must study and learn from Gaza: that despite the horror of genocide and despite Zionism’s belief that its policies will produce a society that reflects its own brutality, the moral fabric of Gazan society has remained remarkably intact for a long time.

This does not mean that it did not shake or crack. Yes, groups of exploitative merchants emerged, and organized crime harmed people just as much as the occupation did. Wasim referred to his bitter experiences with them. But what did not happen was total collapse.

This society remained committed to its self-image, its Palestinian and Arab identity, and its moral and cultural system. A significant segment of society does not want to give it up, as if it were Wasim’s answer to the philosophy and meaning of life, but on the scale of an entire society, on a Palestinian scale.

The impact of death was evident in Wasim. Everything was urgent, rushed, as if life itself was rapidly narrowing. He was running, literally, pursued by the Zionist death. He urged us to hurry up and publish the book, because he didn’t know if he would live to see it. I would ask him about his daily sustenance while he was writing, at the height of the famine, and he would reply: a piece of bread made from ground lentils, or some rice. Nevertheless, Wasim persevered. He wrote, not only to survive, but to awaken a duty in us.

This testimony, with its awareness, logic, and vivid embodiment of the image of the intellectual and the role of culture that philosophies have long theorized about, is not merely documentation. Rather, it is a message from the depths of the Valley of Death, from the hell of genocide, to Arab society and humanity. It is a message that says that death, even on this scale, has not stripped Wasim, Gaza, of our value system. They did not abandon dignity, bravery, diligence, solidarity, pride, patriotism, and resistance. This leaves each of us facing our great moral and national question: we who live within the comforts of life and the whirlwind of consumerism, what is our excuse?

* Arab writer